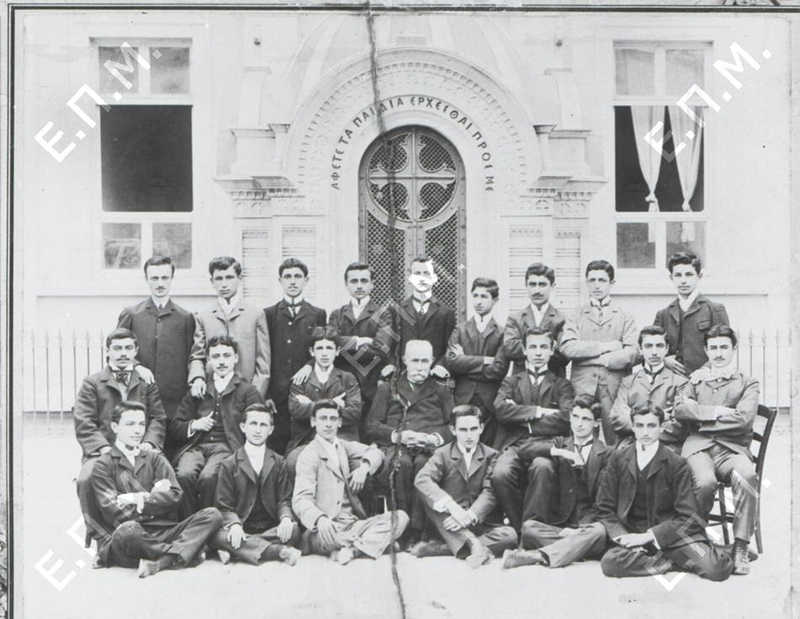

In 1922 and after the end of the war events that occupied the Balkans and especially Greece and Turkey during the decade 1912-1922, the Greeks of Asia Minor and Thrace were forced as a result of international agreements to move away from their ancestral homes.

As early as 1829, many Pontians fled to southern Russia, and their number in 1953 is estimated at 515,000. The Greek Pontians before the outbreak of World War II moved to the interior of Russia and thus mostly lost as a dialect and as a nation, but most of them, ie more than 400,000 went to Greece.

The settlement of refugees in Greece had taken three forms:

a) They established new settlements in the province as farmers, constituting almost entirely the population of these settlements.

b) They mingled with others, either natives or refugees from Asia Minor and Thrace, creating new settlements or clinging to existing ones in which, however, the Pontic element was numerically superior to other population groups.

c) They mingled with others, either natives or refugees in new or old settlements but were a minority.

Regarding the area of Thessaloniki, pure Pontian settlements were: Oreokastro, Nea Santa, Petroto, Prochoma etc.

For the prefecture of Serres: Metalon, Anatoli, Neochori, Akritochori, Byronia. Platanakia, Kastanousa etc.

For Athens: Nea Ionia, New Philadelphia, Nea Smyrni, Kokkinia, Drapetsona.

The above refugee settlement of the Pontians clearly drew a number of consequences for the dialect, which are described below:

– 1. In settlements purely Pontian or with the Pontic element in the majority

The Pontic dialect was influenced by the various sub-dialects of Pontus, because as is well known in Pontus there was not only one dialect, but many which although they had common elements but on the other hand were separated from linguistic and grammatical data in places. See M. Triantaphyllides (Modern Greek Grammar 1st volume 1938, pp. 287-295)

The appeal itself involved the inhabitants of Pontus and their settlement in Greece was rarely done with inhabitants of one and the same village or region. It is therefore understood that these admixtures of the populations of Pontia in common settlements, but coming from different regions, led to an alteration of the special features and characteristics in the local idioms and in the rendering of the language in its daily life. This effect of one idiom on the other brought as a logical consequence the non-authenticity and authenticity of each dialect.

– 2. The same happened in the settlements where the Greek Pontians settled with other refugees from other regions such as Central Asia and Thrace, with tendencies to move more and more each local idiom from its authenticity.

– 3. However, in general, where the Pontic Greek element was found scattered, it accepted the influence of the modern Greek language to a great extent, and this through the native inhabitants and especially with the press or other means of communication of social life.

WHAT CONTRIBUTED TO REDUCING MOUSE DIALECT PROMOTION

WHAT CONTRIBUTED TO REDUCING MOUSE DIALECT PROMOTION

α) In order for the Pontians to be able to communicate with other Greeks in their daily lives, they avoided using their dialect as much as possible.

(..Even we experienced this violence, not to speak our language, the one we heard at home, because we would have problems at school and this would create difficulties in our later professional development compared to other children.

What does all this mean for the native Thracians, Cretans, Cypriots, and Vlachs whose children still retain their language idioms?

I wonder whose linguistic idiom is closer to the ancient Greek language, and who should be proud to speak his language instead of being ashamed that circumstances forced him to move so violently away from it?

Nice examples such as the stone, the lalia, the ofid ‘, the arcon, Opse, and the snow’, which were replaced by the stone, the voice, the snake, the bear, yesterday, the snow !! ).

β) Due to its nature the Pontic dialect had many peculiarities in pronunciation, form and syntax, and because it was not understood by the rest of the population, it was considered by the Pontians better not to be used, and let it not be hidden in any way to mention the rendering to the Pontians of abusive illegalities. and characterizations by the native Greeks, because of the incomprehensibility of the language they used. Contempt was a real element and an obstacle faced by the Pontians at all levels of their lives and was the basis for stopping any development in areas that as a people had the gift to emerge.

They had even reached such a point that they did not admit that they came from the regions of Pontus but sometimes from Central Asia or elsewhere.

The Pontic dialect was mutilated daily from the first moment of its refugee settlement in Greece.

THE PHENOMENON OF “REVOCATION”

Immediately after the exhaustion of the first and immediate material needs e.g. food, shelter, work, and especially with the poor living conditions of the Greek Pontians, the need for revocation was created in them and as a result the spiritual people (Greek Pontians) were to implement a plan of effort and strategic action in order to save its prosperous culture. The lack of an official authority to undertake this work prompted a small number of Pontians on the initiative of Metropolitan Chrysanthos of Trabzon to establish the Pontian Studies Committee in 1927.

Its purpose was the collection, study and publication of linguistic, folklore, and historical material concerning Pontus. The committee was the only association that dealt scientifically with the collection and investigation of the Pontic dialect. In fact, the problems faced by researchers with the dialect were varied and different in terms of time before and after 1922.

Indicatively mentioned:

– The idiom should not have been understood as genuine after the settlement of the Greek populations of Pontus in Greece because it had undergone significant alterations,

– The material that had to do with the periods before 1922 had to be collected, in order to have a reference to the authenticity and authenticity of the speech

– The need to collect material was imperative due to the conditions that threatened the corruption or extinction of the language idiom, and this clearly automatically created another need, the existence of special collectors and qualified persons for this work. But where would they be? The then official state was in complete weakness to help in this direction.

– Any recording made at that time was far from the original because it was made with sounds and linguistic elements of the Greek language, which did not at all reflect the peculiarity of the Pontic dialect which requires a special parasignificant to be rendered.

Automatically another need was created, namely finding a technique in recording the dialect.

D. Economides together with I. Valavanis and M. Defner created special symbols for the recording of the dialect.

Examples: (Ψ) fat is pronounced like French pch as psia (souls)

(X) thick is pronounced as »» ch »» chion (snow)

the (Ξ) »» as »» kch ksino

(ksino)

the (Α) whenever it gives a plural it is pronounced like (yia) π.χ. adelgfia.

Of course, parasimantics also imposed a special type of writing that attributes to the spoken word the special idioms of Pontus, that is, χ is written χ̌, ψ as ψ̌, etc.

The director of the Arch of Pontus, Archimandrite Fr. Anthimos Papadopoulos transferred his experience to the present work and solved many of these problems.

– He set as a limit the recordings that had been made before 1922.

– He ruled out the idiom that was formed under various conditions in Greece.

– Something similar to what had been done for the Historical Dictionary of the Academy of Athens.

– Created new typographic elements that would facilitate the recording of the dialect, based on these rules was the historical spelling of the Greek language

– The problem that collectors would face was also visible because they too were subject to many influences and their work could not be considered genuine due to their weakness and lack of specialization in recording.

– The collectors recorded material mainly from the areas they came from, and it was not possible to record material from all the areas of Pontus.

– So we found ourselves in front of this tragic consequence of having almost no record of several areas or regions of Pontus

– On the other hand, the demarcation of 1922 alone as a basis for the study and recording of the material had lost the data of the study of the effects of the other linguistic idioms in the Pontic dialect.

The single recording on the other hand of the particular idioms deprived some of them of their very special form and structure with the result that they were quite similar to others that did not have as much in common with each other as it finally seemed.

For example, there is no record of the dialect of Sinope and the idioms of the inner Pontus.

Another big problem was the loss of the first generation of refugees, which might make it easier to solve some of the above problems.

(*) The term Pontiki is now more tested but does not exclude the use of the term Pontiaki which was of course established later.

SOURCE: kotsari.com